Information theorist Claude Shannon in 1950 outlined a theoretical procedure for playing a perfect game (i.e. The prospect of solving individual, specific, chess-like games becomes more difficult as the board-size is increased, such as in large chess variants, and infinite chess. Although Losing chess is played on an 8x8 board, its forced capture rule greatly limits its complexity and a computational analysis managed to weakly solve this variant as a win for white. The 5×5 Gardner's Minichess variant has been weakly solved as a draw. A winning strategy for black in Maharajah and the Sepoys can be easily memorised.

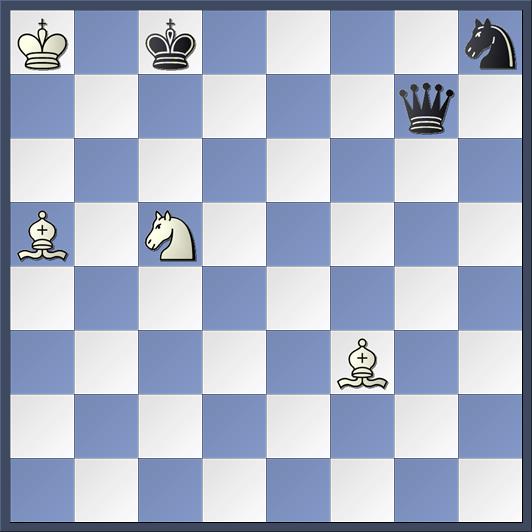

Some chess variants which are simpler than chess have been solved. Therefore the second player can at best draw, and the first player can at least draw, so a perfect game results in the first player winning or drawing. The second player now faces the same situation owing to the mirror image symmetry of the board: if the first player had no winning move in the first instance, the second player has none now. In this variant, it is provable that the first player has at least a draw thus: if the first player has a winning move, let him play it, else pass. Chess variantsĪ variant first described by Shannon provides an argument about the game-theoretic value of chess: he proposes allowing the move of “pass”. Such a position is beyond the ability of any human to solve, and no chess engine plays it correctly, either, without access to the tablebase. One example is a "mate-in-546" position, which with perfect play is a forced checkmate in 546 moves, ignoring the 50-move rule. One consequence of developing the seven-piece endgame tablebase is that many interesting theoretical chess endings have been found. Tablebases have solved chess to a limited degree, determining perfect play in a number of endgames, including all non-trivial endgames with no more than seven pieces or pawns (including the two kings). (In this example an 8th piece is added with a trivial first-move capture.)Įndgame tablebases are essentially backward extensions with additional pieces of elementary mates known since ancient times, stored in a structured searchable disk database. Calculated estimates of game tree complexity and state-space complexity of chess exist which provide a bird's eye view of the computational effort that might be required to solve the game.Ī mate-in-546 position found in the Lomonosov 7-piece tablebase. Progress to date is extremely limited there are tablebases of perfect endgame play with a small number of pieces, and several reduced chess-like variants have been solved at least weakly. There is disagreement on whether the current exponential growth of computing power will continue long enough to someday allow for solving it by " brute force", i.e. No complete solution for chess in either of the two senses is known, nor is it expected that chess will be solved in the near future.

In a weaker sense, solving chess may refer to proving which one of the three possible outcomes (White wins Black wins draw) is the result of two perfect players, without necessarily revealing the optimal strategy itself (see indirect proof). According to Zermelo's theorem, a determinable optimal strategy must exist for chess and chess-like games. combinatorial games of perfect information), such as Capablanca chess and infinite chess. It also means more generally solving chess-like games (i.e. Solving chess means finding an optimal strategy for the game of chess, that is, one by which one of the players ( White or Black) can always force a victory, or either can force a draw (see solved game).

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)